Tuesday 31 August 2010

From Tom's in London

Kitchen at Tom's in West London, after a day of talking and mentoring. Tomorrow to Kingston and to the BBC. Much warmed. This is just brief on Tom's computer.

More late tomorrow.

Monday 30 August 2010

Hailstorm, Sunday afternoon, 29 August 2010

The rain was heavy, grew heavier, then the thunder started in and, within a few moments, the hail began to fall, rather big hailstones, very big ones, dense, breaking, pounding on the skylights. The top photograph shows the street outside running like a shallow river with an ice floe shattered into a mobile mosaic drifting down the middle.

The whole thing lasted about half an hour then started to clear and within an hour it was sunny again. But cold. It is August after all. I am sure there must be some ancient weather saw for this, such as:

When in August falls the hail

Closely following on rain

To beat in fury on the pane..

Prepare to bring out spade and pail

Let Dick the Shepherd blow his nail.

Let all the weather forecasts fail.

Let traffic crawl as slow as snail.

Let stores prepare a Christmas Sale...

etc etc ad inf

Reading translation - Hey, Big Spender

Read, chosen and posted my long list for the Stephen Spender to organiser Robina, who will then inform all four judges of everyone else's list. Then a jolly day in London to thrash things out.

There are three categories: 14 and under; 18 and under; and Open.

Naturally I don't want to give any clues to my own list at this stage so just to note: last year La Fontaine was leading the junior brackets, this year its Catullus. (What's the world coming to, I ask you?) In fact Catullus is this year's poet of choice with some thirty poems across all ages. Rilkes are doing well as are Verlaines, Rimbauds and Baudelaires. Goethes are down this year, Neruda hangs in there, Ovids are steady. Having won the World Cup the Spanish are coming strong. The usual suspects. Dante has been playing for Italy a long time now and looks likely to go on but gets strong, if melancholy, support from Leopardi and Pavese. Good as ever to see the Dutch and the Polish. But there's Portuguese, Arabic, Kurdish, Afrikaans, modern Greek, Yiddish, Serbian, Hungarian, Chinese, Japanese, Welsh, Russian, Turkish, Old Norse, Danish, Gaelic, Irish, Bengali, Gurmukhi, Anglo-Saxon and even Romansh. Sapphos are on the rise in the Ancient Greek market.

There is some rather brilliant work in there and poets I have never come across.

I read and read then one or other piece of work leaps up and slaps me right across the face. Tomorrow night to London for Wednesday at Kingston University for this.

and a quick trip to BBC World Service at lunch time to record this (to be broadcast Sunday and on BBCi, links to be provided),

Sunday 29 August 2010

Sunday Night is... A hail storm and a wonderful life

In the second break today - lunch break - it started raining ever more heavily, then the thunder broke in great groans and blusters, and soon the noise of the rain on the various skylights (three in the house) increased and, behold! it was hail, big hailstones in August, crushing the street, turning white, a soft petalled mosaic of ice oozing through the street, the whole flood rushing past us. Not quite like this, but close:

Now the sun is out, the weather being temperamentvoll, but the wind remains a touch frantic, a little over-insistent. And so this Sunday I wanted to turn to Fred and Ginger, but found Sinatra, then Billie, then Judy Garland, then this, not quite music pure, but rather literally off-beat, where all ends gloriously well.

And so to dive back into the the translators' own pool - the Big Spender.

Some questions: indulge me...

I didn't post yesterday as I am madly reading through the Stephen Spender competition entries - 347 translations of poems from various languages. Life can be hectic at times chez Szirtes and the competition got squeezed into a week or so. Besides one can only read poems for a few hours before the instruments go blunt. In the first break from reading I received a small group of questions from a student (not one of mine, and not local) by email. They were so intelligent and to the point that I took my break by answering them. I post the questions and replies because it is useful for me to remember what I said about these things and the blog is a way of remembering. Then I'll write another post. So:

How do you decide on the form a poem is going to take? At what stage in the creative process are things like rhyme, rhythm and structure (or the lack of any of the three) decided? Do you deliberately choose them, at the outset, or do they evolve as you write?

It depends. When I am writing a sonnet I know the form before, as I do with a number of other forms, like the canzone, which I tried because a friend (the poet Marilyn Hacker) drew my attention to it. A sonnet has fourteen lines, a canzone has sixty-five. A canzone is more demanding because the line-ending pattern is set to high-intensity repetition, while there are various forms of sonnet and one can move the versions around so what you do still registers as part of the sonnet family. There are standard forms, including terza rima, sestina, rondeau, villanelle, the Villonesque ballade (as in The Grand Testament), the acrostic, the mirror form, the Easter Wings form in which there are clear rules, some of which, in some cases, may be modifiable. Personally I like it when the form is not too four-square and steady - I prefer it rocking a little, even on the edge of breaking up but still holding together.

There are other verse forms that I have improvised or even possibly invented, as by chance, usually, in the case of a new poem or subject, when there is no direct precedent in what I have already done, that is related, In these cases I genuinely don't know what the form is going to be before the third or fourth line is done. Sometimes even then, the poem goes quite another way - for example, an unexpected short line might appear that looks right, and then the form moves on to something else, possibly a song form.

The proper answer then is that sometimes there is a decision (if you write a sequence of sonnets, then each part has to be a sonnet of some description), other times it evolves, but generally by the fourth or fifth line I know what the eventual shape will be.

Furthermore, when you constuct a rhyme scheme, does it come naturally or do you have to plan ahead?

I never plan ahead. Planning doesn't work for me. I improvise and accept or reject my improvisations. I don't mind beating up sonnets: they can stand it. Terza rima is more demanding, but all I have to do even then is just to think a little ahead and feel the narrative shape developing. That is an instinctual reaction - by instinct I suspect I mean an internalised form of learning, the way a pianist will hit a chord, not because he thinks about it as a separate and distinct act, but because his fingers are aware of certain possibilites. There isn't a distinct conscious thought to decide the fingering. If he is an improvising kind of pianist, he wants to be surprised. And so do I. Surprise makes things new. In fact I firmly believe that a poem has to surprise the writer, that the true poet cannot know quite what he is doing but discovers it. Where the form is ornate, say in the canzone, I make the decisions as I go, but consider, as I choose my end words, whether I might or might not be able to live with them to the end. The key to writing is listening. I mean listening to the poem as it forms and responding to it.

Do you ever write with a particular political or cultural aim in mind? To make a point, as it were (as opposed to personally exploring an idea)?

I go with Keats who hated poetry that had a palpable design on the reader. I don't mind versifying - in fact I enjoy it - but my inner ghost is always whispering to me that life is more complicated than a versified slogan or anthem, and that it is my duty to be faithful to that complexity while articulating it as simply as possible, even while improvising and discovering it. I don't write to tell people what I know or think I know (my suspicion is that I 'know' very little), but to find out how the subject sings. People have asked me to write for particular public occasions - wars, commemorations, etc - and I have tried to oblige without betraying my core instinct. I am not there to cheer on or to demand executions. Except, just possibly, as dramatic gestures. Dramatic gestures are interesting in themselves. But beyond that the general principle is that if it is action that is required, then act, don't bleat on like a sheep hoping to attract other sheep.

Who or what would you say have been the greatest influences on your writing, both in terms of style and subject?

There have been various poets that have hit me hard over the years and, like all poets I imagine, I carry the bruises. Some have faded, some don't. First great hero was the French poet Arthur Rimbaud (who I read only in English translation), then it was Eliot, then it was Auden and Brodsky, but these were only the heavy punchers. Then there are the Hungarians from whom I have learned by translation. I would say Rilke, Wallace Stephens, but also John Crowe Ransom and Elizabeth Bishop among the moderns, and Marvell, Herbert, Pope and Byron (the comic Byron) among the historical. As you can see, that's a lot of nice bruises and I haven't mentioned a quarter of them yet.

One of the reasons I think I am drawn to your work is that my grandparents are East European immigrants; how do you think exile and the dilemmas posed by assimilation have affected your writing, if at all?

I do increasingly think so, yes, though it has rarely been a direct 'subject' of my work. I imagine it is a kind of inner predisposition to find things balancing up in a particular way. Assimilation was distinctly an issue for my parents and, in the 70s and 80s was a poetic issue for me, but, again, not as a subject, more as a way of trying to 'speak English' and all that means. I do believe that historical consciousness is a considerable value in the best poetry, but I don't mean by that a set of specific subjects or even allusions, just a sense of the world as a force behind you and a terrain in front of you.

I've particularly enjoyed some of your poems about both Budapest and London; do you feel a particular attraction to metropolises?

Yes, I am at home in urban spaces. I was born in Budapest and my early psycho-geography is the streets, walls, sounds and spaces of the city. I like fields and hills and what people consider natural places, but in some ways the city is my natural space, the rest an excursion.

Equally, you often include depictions of war scenes; do you think being born only three years after the end of the Second World War and living through the Hungarian Uprising left an indelible mark on your writing?

The war scenes were the actual walls and broken statues of Budapest as I saw them in the mid-Eighties. The walls were covered in bullet and shell scars. The statues had lost limbs and heads. It was as if history was engraved on the skin of the place. Those walls fed through into the notional pianist's fingers. I instinctively think history is like those walls. Since 1989 the scars have been covered and tidied in most places, but it's too late - I know they were there.

Finally, I've recently finished reading Auto Da Fe, having only ever heard of it because of 'The Burning of the Books', and I thought it was wonderful. Can you recommend any other East European translations, or similar books, that I might enjoy as well?

Yes, there are others, if by others we are talking novels. Bruno Schulz's 'The Street of Crocodiles', Joseph Roth's 'The Radetzky March'; Antal Szerb's 'Journey by Moonlight', W.G. Sebald's 'Austerlitz', Thomas Walzer's 'The Walk'. And there are those I myself translated of which these three are perhaps the most magnificent: László Krasznahorkai's 'The Melancholy of Resistance' (Krasznahorkai is a living author), Gyula Krúdy's 'The Adventures of Sindbad' and Sándor Márai's 'The Rebels'. Like Canetti, all these authors perceive life and stories in terms of a kind of underlying poetry.

It is a little self-indulgent putting this here - as though anyone was interested! But it is equally false to think people are not interested. And, dammit, I'm interested to see what I say when I open my mouth. Those are the books I first thought of in the last question - no doubt I have missed many others.

Friday 27 August 2010

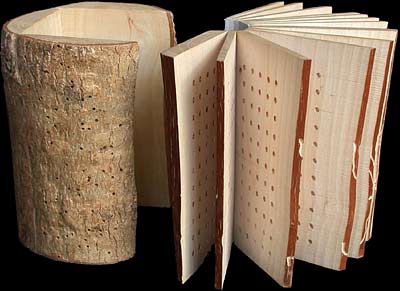

Book Beauty

For a while C and I ran a press together. It was called The Starwheel Press and it produced portfolios of etchings and poems, none of the poems by me, but rather by invited poets - five of them - together with etchings by five artists, of whom C and I were two. The editions were small - fifty-five copies - and were sold by subscription. There were unpublished signed poems by people like Craig Raine, Anne Stephenson, Peter Porter, Kevin Crossley-Holland, Wendy Cope, etc. We sold them at about £15 per portfolio of five: they go for about £200 now (though not from us). There were other one-off publications of which more later, heaven knows when. The portfolios would have been a good investment at the time

The technique required an etching press (the eponymous Edwardian starwheel press), a monotype press (a heavy Golding Jobber, powered by a 1hp motor) a supply of monotype trays, acid baths, and plates of zinc or copper. The etching took place in the cellar, the letterpress in the outhouse. What we sold we ploughed back into the next production, of which there were one a year. We paid ourselves nothing. It was a whole summer's work each time.

It was simple and limited. We weren't perfectionists and we didn't invent anything. Meanwhile, out in the world extraordinary books were being produced. Books like this:

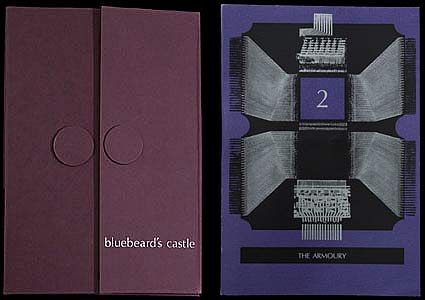

from Bluebeard's Castle

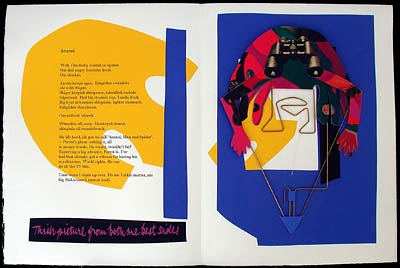

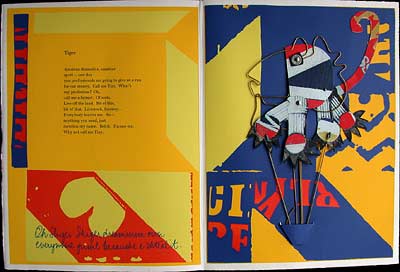

from Anansi Company

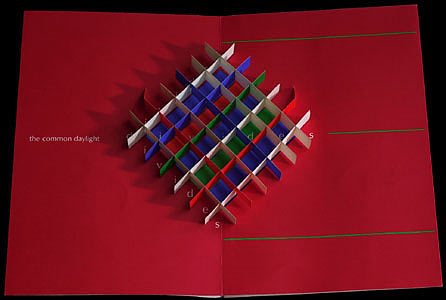

Log Book - Termite Grid

These are some of the products of Ronald King's Circle Press. But there are books involving mirrors, books with blind embossing (amongst them a gorgeous one about babies by Willow Legge, around a poem by Penelope Shuttle), books six foot high, and books in the form of cases, and books that spill or project out and books with removable pieces. And also books produced at Circle Press by people who passed through as assistants and fellow workers.

This is not an advertisement but an act of homage, primarily to Ron and all that he has generated. The point is not that these books are pretty or decorative, more that that they are savagely playful and are an earnest of what book-as-object can be. Because there are wilder shores still than these: hairy books, books that wear clothes, books in shoes, books in bits that assemble and reassemble. Books as sculpture, books as concepts.

But there is, originally, the book, that is usually a vehicle for text, or text and picture, or just picture; the essentially functional book where you turn the pages almost unaware of the book as substance, because it is the words or images that perform for you.

Even so, even among the cheap paperbacks, even among the ephemera, there are books that feel and look better than others. 'Books do furnish a room' as Anthony Powell has it somewhere. I know what he means as most of our walls carry wall-furniture of just that sort. 'Cheap insulation,' as someone else once said.

Cheap and solemn, or cheap and cheerful. Most of our books are of that second-hand company. But it's good to think of proud, joyful and ingenious books strutting around like peacocks, or screaming like children, or singing through wood, each with its own form of sense.

Thursday 26 August 2010

Back late

Rather late. More tomorrow. On beautiful books, and artists books, and the possibilities of books... For tonight, sleep, if I can get it.

Wednesday 25 August 2010

Revising

In this case, intermittently but intensely, the Krasznahorkai translation. I forget how dreadful some passages were in the first version because I was so relieved at getting through them at the time. Re-encountering them is depressing. It's like meeting oneself first thing in the morning, hair all over the place, hangdog look, unshaven, barely sensate.

So you take the text, wash its face, brush its teeth, comb its werewolf hair and wait for that maniacal gleam to reappear in its eyes. You hope for a full moon. Then, once ready, you let it out, allowing it to seek whom it may devour.

Me? I put my glasses on but it's no great improvement. On the road again today, perforce.

Tuesday 24 August 2010

Twenty-third glorious year

It seems the success rate of GCSE passes has improved for the twenty-third year in a row. That is magnificent news of course, especially when one realises how thick those students of twenty-three years ago must have been, and how utterly mediocre their teachers most certainly were.

I wonder what has happened to the GCSE successes of 1987? They must be very near the bottom of the pile now. They couldn't possibly be the teachers of the latest and greatest set of triumphant scholars. They wouldn't have been bright enough.

And think of the degrees awarded back in 1987! The present GCSE cohort must be at least PhD level compared to them.

The future is in safe hands. Meanwhile, I return to contemplating the boxfish, a wholly rationalised structure for the oceans of tomorrow.

Monday 23 August 2010

Edwin Morgan as Translator from Hungarian

My first contact with Hungarian poetry when I returned to it in 1984 was through Edwin Morgan. His translations of one of the greatest of not only Hungarian but European poets, Sándor Weöres formed half of the Hungarian volume Sándor Weöres / Ferenc Juhász in the Penguin Modern European Poets series, the other half being formed by David Wevill's translations of Juhász.

It was Weöres long poem, The Lost Parasol that particularly fascinated me and impressed me, but every one of the Weöres translations was fully alive. I was drawn to both poets in it, but Weöres was more fully within my experiential and temperamental range.

The Lost Parasol in Edwin Morgan's translation begins:

Where metalled road invades light thinning air,

some twenty steps or more and a steep gorge yawns

with its jagged crest, and the sky is rounder there,

it is like the world's end;

nearer: bushy glade in flower,

farther: space, rough mountain folk;

a young man called his lover

to go up in the cool of daybreak,

they took their rest in the grass, they lay down;

the girl has left her red parasol behind...

There are some thirty-six more verses of the same length, the lines tabbed, as the link shows, not justified left. The poem is about the disintegration of the parasol and its return to nature. I can imagine better translations than Morgan's (one always can imagine better) but don't think I could produce one. Nor do I really need one. The translation does what very good translations do: it doesn't attempt to become the original, it yearns and points towards it.

The point was that Weöres's status as a great poet was established in my mind by Edwin Morgan. Like all the Penguin Modern European series, the Weöres / Juhász volume was not only an eye-opener, it offered possibilities.To me, in my position, it offered highly relevant ones.

As the title of the series implies, the minds from which these poems sprang were European, which is to say that their tone and field of reference owed as much to the history of the European mainland as to the shared heritage of Greek and Latin classics, Biblical traditions and the products of European colonialism, which included the introduction of myths, fables and approaches from outside Europe. Modernism was a fully assimilated language to them. It was what they spoke out of experience. They were where it grew up.

In that respect Morgan's instinctive Europeanism was an enormous help. The body of his translation work is a fat volume in itself, and shows he was always curious about those related yet distinct areas to which parts of Britain have at times aspired. The Columbia University edition of Modern Hungarian Poetry (ed. Miklós Vajda, New York, 1977) would have been a lot thinner and a lot less exciting without him. He did more translations than anyone else, followed only by two Americans, William Jay Smith and Daniel Hoffman. He has translations of most poets in the book and instinctively understands them, which is not always easy. He also follows form, not so much as replica but as ghost, throughout. We know what form the originals employed and can sense the way this has created both poem and translation.

Apart from Weöres his other major Hungarian poet is Attila József. Weöres, József, Radnóti, Pilinszky and Nemes Nagy were five of the great poets of the century (one might add some others but would not remove any of those), and Morgan has two of them. His Attila József: Sixty Poems, is, I think the most even and most convincing of the available translations, if only because while others have matched József's form or caught some of his colloquial street voice, Morgan is the one who best knows what József was writing about: urban poverty. His version of József's 'Night in the Suburbs' that begins:

The light smoothly withdraws.

its net from the yard, and as water

gathers in the hollow of the ditch,

darkness has filled our kitchen.

Silence. - The scrubbing brush sluggishly

rises and drags itself about;

above it, a small piece of wall is in

two minds to fall or not.

The greasy rags of the sky

have caught the night; it sighs;

it settles down on the outskirts..

Light assonances, indications of the passage of rhyme, hold together a picture that might have come from one of Morgan's own Glasgow Sonnets. Poor Glasgow, poor Budapest: the tenement blocks in each city support a similar range of feeling. József is a greater poet of this world than Morgan, but Morgan makes József speak and sing in English, and besides, what Morgan offered was breadth and variety rather than visionary intensity. It is wrong to expect from someone what he does not give, especially if it gets in the way of what he actually does give. Morgan understands, quite viscerally, where the visionary intensity in József comes from, and that (as well as art) is what matters.

It is not unusual in Hungarian poetry for the collected works of specific poets to consist of more volumes of translation than of original verse. Morgan has something of that. The Carcanet volume of his translations shows what is possible: the translations are the work of someone who has not simply co-opted those he has translated into a personal project, nor has he set out to imitate everything to the point that we seem to be wandering through a museum dedicated to replica furniture. He strives to understand through similarity, by understanding the nature of the dance and letting it move through him as something familiar, just slightly elsewhere.

Sunday 22 August 2010

Sunday Night is...Brad Mehldau, 'Fifty Ways...

...To Leave Your Lover'. Talking of music on the train from Criccieth to Birmingham with John W, Brad Mehldau came up, so here he is.

As a pianist I was chiefly let down by my left hand, though the right hand was not far behind. My inability to manage cross-rhythms through my fingers was similarly disappointing. Behind this lay a sheer incapacity to count at all. Despite these desperate handicaps I played piano for some five years in the blissfully forgotten jazz-standards combo, Steddy Eddy and the Metronomes. I wouldn't call us exactly third-rate. Seventeenth-rate would be closer to the mark.

Mehldau, on the other hand, has an amazing left hand - independent, powerful, beautifully subtle in rhythm, the whole delicate and meditative when the piece demands it. John suggested he was the heir to the great Bill Evans, my all time favourite jazz pianist. Mehldau might be the heir: it might be so. Here is Evans playing Nardis at a private house in Finland in 1970. It's like a scene from a movie. He declines coffee at the end. They have to get going.

Kids, Bill's posture is all wrong. Do not try this at home.

Bill Evans - p

Eddie Gomez - bs

Marty Morell - dr

Saturday 21 August 2010

Home again

On the last morning - everyone wanted another workshop and discussion - I gave people the game where they have very quickly to make up ten words, then pass them, so the receiver can use them in a coherent piece of writing. The result is some very clever pastiches and general laughter. It's a relaxant after a lot of intensity, but it's also an interesting point of discussion.

First, because it is hard to make up words that don't sound like anything we already know. The known words haunt the fabrications. There are a number of possible contexts waiting for them all, but not necessarily the same one in a group of ten.

Secondly, because, through the game, we get a glimpse of the fragility of the whole language system. Words are strange, and so are their occasions. It is, in other words, a comical alienating device.

Thirdly, the contexts into which the words are made to fit, demonstrate our automatic recognition of genres. There are fairy tales, science fiction stories, newspaper reports, threatening lawyers' letters, recipes, list of instructions for assembly, romantics scenes and dictionaries, as well as many more. Each of these has a generally recognised manner and we take to them so readily we can spout them at will. In other words we can register tones with considerable precision. In the same way we can hear poetry as it both relies on accepted modes and yet tries to slip free of them, turning them round on themselves.

Most of poetry is intense listening to the music made, not only by the consonants and vowels, but by the various registers as they struggle to embody an apparently important experience half recognised and half unknown - unknown because it cannot be known before language has set out on its journey towards it without quite knowing where it is. In that process it may arrive somewhere else even more interesting - has, in fact, to arrive at something more interesting to become a poem, which is why poems are improvisational acts.

But of course the game is only a game, and many other activities could demonstrate something similar, it's just that it is good to laugh and think a moment about what it it is that invites laughter.

And the best thing - something I have observed time and again - is that people can write much better in a few days once their attention is re-directed. I really do mean much better. Imagine someone having tried to get into a house through a door that won't open, and someone says, but there's another one, wide open, if you go round the other side. And the other door is obvious enough once you've gone round the side.

It doesn't mean you immediately become a great poet or even a good one - all it means you recognise better what a poem is and how it might come about. Because I firmly believe that most people know what poetry is, in one form or another; that it is a form of meaning they already understand. It's not clever stuff, it's not morbidly sensitive stuff - it's a way of coming at things and seeing them afresh, washed clean by language.

Friday 20 August 2010

Edwin Morgan

It is hard to write a proper appreciation from where I am, in the midst of work, but I hope to write something about Edwin Morgan, who died yesterday at the age of ninety, on my return. I met him just once for any length of time, when we were two of the three judges of the National Poetry Competition some time in the Eighties (Jonathan Barker was the third judge). It was a long session and the winner came up late and sudden, unexpectedly after having lurked in the pack.

I had reviewed his Poems of Thirty Years and was, at that time, uncertain about one aspect of it. I wrote in enthusiastic praise but hinted that I had missed what I think I then called, 'psychological complexity' or some such thing. But that was my own immaturity. It is easy to miss in others what you yourself experience as a pressing need - it seems important because you personally desire it, and you want more of it elsewhere. In fact you want it to be evident everywhere. But why, after all, should it be? And of course it might be there, but not quite in the form you yourself want, or even recognise. If I have recently been deemed to be - generally - a generous critic it is because I am more aware of my own possible limitations as a reader - you say what you think but you don't take what you think to be the last word.

What I did praise, and couldn't help praising, was the breadth, the energy, the willingness to be full of everything that was exciting. Many people have spoken of his warmth and generosity and these qualities were to the fore in the poems. It is interesting that experimentation, an enjoyment of the gifts of Modernism, and a willingness to enter areas that might or might not be central to your concerns, is more characteristic of Scottish than of English poets. It is, in some ways, a great sense of contact with the European mind and way of thinking. In England there is an earnest desire to find your heartland and live exclusively there - which might, after all, be another way of saying, Know your place. It is a kind of solemnity that underlies aspects of behaviour, and may be class based. People sometimes frown on what they regard as merely 'a lark', but which may be something more like 'high spirits'. Inappropriate behaviour.

High spirits is energy willing to forsake its own manners. Edwin Morgan was full of them. I can't talk about the characters of people I have never properly met - in the case of artists, however, there is a perfect right, indeed an invitation, to talk about the character of their work in terms of human character. It might in fact be a truer impression of the human being than the impressions one gets in life, which is full of moods and circumstances. In that sense Morgan was brilliant, sparkling, substantial and moving - a proper human being with heroic dimensions.

Here is a poem of his I have sometimes discussed with students. It is one of the Instamatic Poems, where the poet places himself in the instant and just watches. It's just that the light sensitive surface of the imagination is sensitive to a great deal else:

Instamatic

Glasgow 5 March 1971

With a ragged diamond

of shattered plate-glass

a young man and his girl

are falling backwards into a shop-window.

The young man's face

is bristling with fragments of glass

and the girl's leg has caught

on the broken window

and spurts arterial blood

over her wet-look white coat.

Their arms are starfished out

braced for impact,

their faces show surprise, shock,

and the beginning of pain.

The two youths who have pushed them

are about to complete the operation

reaching into the window

to loot what they can smartly.

Their faces show no expression.

It is a sharp clear night

in Sauchiehall Street.

In the background two drivers

keep their eyes on the road.

Thursday 19 August 2010

Ty Newydd 4

So today we went for a walk down to the estuary, the wind lightly blowing, clouds pending but not due to rain for a few hours. Cows in the field, sheep by the river, swans folding and unfolding, and the constant hiss and shimmer of the sea where the river runs into it.

The task to walk down there, chatting if we like, then once by the water, to remain silent and simply look, listen, touch, smell, and possibly even taste, while thinking. No pressure, simply notate. We are primed for this by a discussion of the work of the artist Francis Alys, specifically his fox in the gallery project...

...and by reading Robert Minhinnick's Forward Prize winning poem, 'The Fox in the National Museum of Wales'. We are to be foxes of a sort, or we are to set the foxes of the mind stalking through the gallery of 'sea art'. A tribe of thought-foxes.

So there we are, silent. The estuary is wonderful, but it leaves me gobsmacked. That is not to say I am not writing, but what I am writing is inadequate and I know it. Nevertheless I write.

Why is it inadequate? The whole syntax apparatus seems wrong. Lines in which one thing is compared to another seem contrived. Why is that? It may be because the sea is not my element (a landlocked country's capital city is my egotistical sublime), or because nature always takes me back to primary school nature walks where I hardly understood the language let alone tell the difference between one green thing and another. So the problem might be in me.

On the other hand it may be - or may also be - something else. It may, for example, be because it's all too primal and beyond language. Or maybe it's because it has been written and painted and sung so often the beach is all too crowded and I can't begin to hear the sound that sings to me. I other words it is too full of language. Others might be having that trouble, I imagine. Sheer size. So I wander along and fill pages with notes. Then I stop, skim a couple of pebbles, and start assembling a rather naff Andy Goldsworthy set of stones in a pattern on top of other stones. For a moment I think of Jewish funerals, then I go back to arranging the pebbles by colour so they make a kind of palette. Nice but pretty. Overcrowded. I feel the minimalist urge. It's all a little voulu, as things stand, I think, much like the effort of shoving this enormous phenomenon into syntax and simile and metaphor and rhythm, in other words into poetry. It's like trying to empty the sea with a jam jar.

What we need is a new language, I think, or at least the beginnings of a glossary, and I start to put down the categories for which I would need new vocabularies. These include:

ways of moving; textures; sounds; colours; densities; formations; paces and rates of movement; gestures; tones...

It is with these I return, along with the others, to compose something. What I compose looks a little like that list, a dictionary in fact with terms, phrases and words that might be grouped together under each category. I add some new categories and remove some possible overlaps. Some I just forget. Then, because this looks exactly what it is, a list of prose items, I play with formatting on the computer - putting in tabs and spaces, letting the words dance a little across the space of the page. I suspect this is cheating, but, all the same, it is faintly encouraging. There is about a page and half of it, and it's not exactly a poem. I can't format the blog as I would a page, so you'll have to imagine how you might want to space it, but it begins:

Ways of moving:

Pulse of wind, press of wind (as in the fingers of wind gently pressing against eardrum), swandip, swanbulge, swanstretch, peeling (as in gull peeling, as in peeling off the horizon, breaking into bribs and blebs,

Sound:

sussuration, sibilance, hissing, severance, slobbing, sisterance, haw, ha, hm, hrum, squak, squirk, settling, the sudden cry of a low- flying plane

It progresses through:

Textures:

hair, skin, bullet, scraped, dinged,

screaming, phlegmatic,

buggered.

Densities:

breast,

haunch,

nape,

groin,

wire,

chain,

gravelled,

dreamt,

denser / dreamter

densest

And ends:

Homages: human offerings, (the deodands):

bright helpless bits of blunt blue,

startled yellow, intimated pink,

the fadings, deformations, ephemeralities,

evidences, the beginnings of a palette.

Food: the floating egg,

zabaglione,

hundreds of thousands,

porridge,

soaked bread

grits,

…pure Quality Street.

Broader concepts to be dragged kicking and screaming into language: the surprise of being there at all, of anything being there at all, of being there, of the concept of 'there', and, more intriguingly, the concept of a straight line of cloud pressing lightly down on its bed of language, still working out its etymologies.

All formatting lost, and with whole sections missing, the text is pretty naked and unresolved, but there's something ticking there. It's only a parody of a dictionary and a language, but it is genuinely trying to get to grips with something, however hopeless.

A shorter lunch break and longer tutorials - but very encouraging ones. The students have written some good sea poems (better than I could manage in some cases, but then mine isn't precisely a poem, and Pascale's is wonderful) and their work over the course has come along in leaps and bounds. I feel quite exhilarated by this. So, I feel, are they. There's a good shape to the week.

But it's pouring now, the sky one great grey sponge. It looks as though it intends to hang around for the evening.

The Fish-Man poem

By overwhelming public request (ie Diane), here is the draft of the poem written according to the shaman's coat principle. I'm putting it up on the front page of web site too, to lead its own life there for a while, as this one disappears into the archives after five days:

Fish Music

For Pascale Petit

He struggles into his borrowed human skin,

the one he wears for special occasions

with the sewn-in dinner jacket and polished patent feet.

He brushes off earth and other traces of night,

smells the remnant darkness on his sleeve,

bends back the fingers that constitute his living,

and picks up the instrument. His mother is listening

in the next room, holding her breath for him,

the breath she has been saving all her adult years.

After the skin, the fish scales. One must glitter.

One must swim through the day. He flicks his tail

this way and that. He makes the first sounds,

those scraped sighs that are the sign of his well-being.

‘I’m ready,’ he says, his eyes glassy and round.

‘I’ve got my gills on. The whole amphibian kit.’

The music begins. The sea waits by the door.

Both skin and scale are glowing. The neck he wears

is just a little loose, he must tighten it.

The chin has worn away on his left side.

The music slops about inside his belly a while

then creeps upward blowing through his ears

into the room and hard against the walls.

Now he is swimming. He sees the music

floating in the tank of the room. He must practice harder.

It is his food after all. He can feel its strands

slip between his fingers, now silk, now knife.

It smells wholesome, of water, night and skin.

‘How does it sound?’ he asks her. ‘Like salt,’ she says,

‘like salt and damascene.’ Her fancy talk, he thinks.

It’s not his skin, he knows that. The dinner jacket

is of another era. Too many buttons on the waistcoat

of the flesh. Too much blood in the fibre, none of it his.

But music too is skin. He wraps it about him.

He’s hardly there: half-fish-half-man is elsewhere,

in the bone beneath a skin that’s not his own.

Each living thing has its own element, he thinks,

and even this old skin belongs to someone.

It has, in fact, received one or two very minor editions already, but I'll let it sit and dry itself out for a while. Once it has dried out it may look different and might need either editing or disposal. This blog is full of transitory, semi-public material. If it's dreadful I'll let it embarrass me in future years.

Wednesday 18 August 2010

Ty Newydd 3

Pascale's morning. We look at poems on paintings by Moniza Alvi (Mermaid and Eine Kleine Nachtmusik) and Sharon Olds (The Unswept Room) and discuss them in terms of their relationship to the paintings on which they are based. The Dorothea Tanning painting that is the point of reference for Eine Kleine Nachtmusik is or is not darker and more disturbing than the poem, which is or is not more a celebration of energies. We look at imagery that is adapted and that which is invented. Then we move on to shamanism, looking at a Russian shaman's costume.

We consider the list of categories under Mental Imagery from the Princeton Encyclopaedia of Poetry and Poetics, consisting of: Visual; Auditory; Olfactory; Gustatory; Tactile; Organic; Kinesthetic and Synaesthesia. We are asked to consider how far we make use of these.

Finally we move to Joseph Beuys, his felt suit and his constant use of animal fat, which, Beuys maintained, related to his rescue by Tartars after the plane he was piloting in WW2 had crashed. The factual basis of the story has since been questioned. Some think that only makes the story better, a secret part of me thinks I prefer truth, thank you. But then I like the fantastical voyages of Purchas and Mandeville, so a tall tale - what Yeats had as stiltstalking, Yeats being keen on his lying warty boys - is not without attraction or power. And yet I like to know there is a distinction between subjectivity and the world, between fantasy and fact. I guard this prosaic part of me with a certain jealousness, considering it a valuable ballast to my irresponsible warty imagination.

We are to reconsider the various forms of Mental Imagery and are given a poem to write in which we can invent fantastical shamanistic clothes for someone we know, or indeed ourselves. We are encouraged to move between the senses listed under Mental Imagery, employing a variety of them, moving between them. Ways are suggested of organising such movement. We have some twenty minutes.

This is all exciting stuff, so I go off to my room and write a thirty-seven line poem in which a boy-man wakes to put on a human skin that is not his own. Furthermore, it has a dinner jacket sewn into it as well as patent leather feet. After donning the skin he puts on a second coat of fish-scales because, after all, 'One must glitter'. Half man-half fish, he picks up his instrument (a violin though it is not named) and prepares to practice with his mother listening through the door. The music materialises. He asks her opinion. She says it sounds 'like salt and damascene'. Her fancy talk, he thinks. He is not altogether comfortable in his clothes so puts the music on instead. Music is another form of skin. His skin is not his own. But 'Each living thing has its own element, he thinks / And even this old skin must belong to someone.' The End.

It's a pretty mad thing with some memories of my brother practising his violin (including his fish scales, of course) while my mother listened outside the room, but I like it. It's bursting with sensory overload but it is consistent and, in its way, disciplined. It needs some editing: it has tumbled out pretty fast, but then so did all the poems of The Burning of the Books, and, come to think of it, all my best work in the last ten years or so. I check to see that there is a ballast of actual fact in there though I am perfectly aware that my brother, who really did practice the violin and is in fact a violinist, is not half man-half fish.

And did I ever tell you that when our car crashed in 1956, in the heat of the revolution, I was nursed back to life by a wandering band of benevolent garden gnomes who wrapped me in old toffee wrappers and discarded fast-food containers? Honest. This will go down in the official biography.

I'll put the poem up after a few days if it still appeals. The splendid thing is that everyone wrote splendid things. Constraint plus fantasy is liberation from the less manageable obligations that society - even one's own solitary society - requires and imposes

Then lunch and the tutorials. Some very good work there. And Philip Gross has arrived to read tonight.

Tuesday 17 August 2010

Ty Newydd 2

A heavy workload day for me despite a not particularly good night (I rarely sleep well on the first night away) so I was closer to being a wreck than I could afford to show.

But once I start something it generally carries me because it is interesting in itself. So the session begins with a long discussion about what we understand an image to be, what it does, how we seek images and how we might find them in representations of the world, specifically in visual art. Generally, I just ask questions then comment around the answers. We talk about what kinds of visual art lend themselves to being written about, and the forms the writing can take, starting from the notions of art history, art appreciation, art theory, journalism, conversation, moving on to what we think of as creative writing - fiction and poetry in particular. Why do we respond in this way? What are we hoping to achieve? What obligations do we feel to the art object and in what way might we be free to go our own way?

Is there something second hand about it all? Like bumming a ride? Is ekphrastic writing a lesser form because it starts out from that which has already been digested and formed? Is 'life' the primary experience, and 'art' merely a secondary one? Is there such a thing as primary experience and secondary experience?

On the other hand, do we not find that in confronting 'primary experience' we bring to it a great deal we have absorbed at secondary level, so what appears primary is already a 'subject'? We know about things before we meet them. They belong in our field of real and imagined knowledge. In that respect there is no real primary and secondary. The 'secondary' constitutes 'primary' in that it confronts us. This leads nicely on to the coffee break and what lies beyond.

*

The second half of the morning was spent on photography, which Pascale and I had agreed would by my area for the purposes of the course, while she dealt primarily with the various forms of what are referred to as fine art - paintings, sculptures, installations, etc. Here I used two central texts - Barthes's Camera Lucida and excerpts of an interview with the photographer, Diane Arbus. There is a close similarity between what Barthes and Arbus say about photography, and what they both say can be applied very well to poetry too. So we are looking for a poetics of photography that is also a functional poetics for a writer.

I set a brief exercise, to imagine a portrait photograph and to see it as Barthes sees it, that is to say in terms of studium (its interest as a subject), punctum (the discovery of an incidental, unintended detail that moves the image beyond subject into the field of the personal desire and possibly even subverts it), and blind field (the surprising unknown place where the punctum might take us). This corresponds with my general hunch that most lyric poems are tripartite - the first part the original scenario or setting that, like the studium, is known in some way, the second part a shift through some detail or association is removed to another place, and the third part that is the reult of of the journey between parts 1 and 2.

But how do we find the punctum? The way a great photographer does, by positioning ourselves in a likely place and hoping to spot it. Experience in poetry is about having a nose for where to position yourself.

The imagined photograph is a good idea though it may be best to specify that it be a photograph of someone not too close to the person. The knowledge of the person can be overwhelming - too much knowledge floods in. But it is just a brief exercise so no harm done. At the end I deal out a photograph to each person. They will take that away and work through it considering the various ways we discussed. I also give a few constraints. The poem must have 13 lines, in other words it will be aware of the sonnet just beyond it, and must contain one set of end rhymes. If 13 lines isn't enough then the continuation must be another 13 line piece, and so on, possibly to form a set.

These constrains are partly arbitrary but contain a suggestion of precedent. The arbitrariness is important because it allows the language to make conditions, and not be too passive. Language for a poet must be like the camera to Diane Arbus - 'recalcitrant'. Dealing with this recalcitrance is what is called technique. Arbus finds the camera recalcitrant but she takes technically very fine photographs. It is her way of dealing with the recalcitrance. This is by no means easy of course, but at the same time I assure people it's no great problem if the poem doesn't work. That's my fault not theirs.

Responsibility is a great killer of the imagination.

Then supper, then Pascale and I do our readings followed by discussion. Then I stay up another hour and a half in a conversation in the kitchen about major / minor, great/ insignificant poetry. Conclusions another time.

Then about five minutes ago a young house martin (or swift?) flies into my room and bangs against the walls. It is magical and endangered. I fear it might hurt itself, I open the windows wide and, finally, it flies out.

There, he is just gone.

Monday 16 August 2010

Ty Newydd 1

A brief one as it is a nine hour journey and I had only about four hours sleep the previous night - what is more it is for me to lead the session tomorrow morning.

The train ride is as beautiful is people said it would be - it's the last four and a half hour stretch from Birmingham to Criccieth. Till then I had been reading, now Pascale's new book, now diving back into Barthes's Camera Lucida. I still don't understand all of it, and sometimes he does that very French thing of saying something mysterious and portentous for the sake of it, which is a kind of puffing up, but what I do understand - that is to say when he is thinking rather than searching for terms or trying to find the mot juste from among the five or six possibilities that each might be juste if I knew what he was directing the mot at, he comes out with wonderful things that are just as applicable to poetry as to photographs, that, for instance, you want to feel that the poet / photographer has found things as if by accident rather than carefully placing them.

The route skirts the sea for hours in Wales and everyone looks out, enthralled. Why? you might ask. It's just water, a lot of it, slightly choppy, sparkling and pulsing. But children, teenagers, adults are entirely focused on it, and every time they lose sight of it then find it again, there is a surge of palpable excitement, that I too feel.

And I think of the word 'surge' which is the first word to come to mind, and realise it is exactly what the sea is doing. It surges towards the land and our eyes and hearts surge towards it, our alien, hostile. ravishing element.And that little word-play keeps me interested for a while, and then there's another surge... There is something significant there, about language and enactment and onomatopoeia and punning. Can language do what the sea does? Has it any alternative but to try?

Sunday 15 August 2010

Two new photos of Marlie

Grand-daughter Marlie, with her dad, Rich, in miniature Star Wars world. Hot off the press.

Before I go off into the wilds of Wales early tomorrow morning. And the wind is truly wild at the moment here in the small town of W. All the 'w's coming together, wild and wind and Wales and W...

A distinct change from last time - alert, curious, amused. And the proportions in motion too, still a baby but part-child.

Yesterday would have been my father's ninety-third birthday. There is an extraordinary gloriousness about life.

Sunday Night is.... Schubert's Winterreise with Bostridge

Gute Nacht, the first of the Winterreise cycle. Romantic suffering pressed through the rusty gratings of the soul, purified and poured into the darkness. The video is a little stagy, a little self-indulgent, as heartbreaking adolescence generally is, but for sheer clarity of melody there is no one better than Schubert.

Ian Bostridge - a little proper, a touch public school boy - but with extraordinary phrasing and fitting clarity, does a passing imitation of Hugo Williams in Schubertian gear.

Ignore the slight cavils above. It is gorgeous, plangent, beyond sentimentality. Original words by Wilhelm Müller, with nice commentary and translators' notes and a lead to a singable translation.

Gute Nacht

Fremd bin ich eingezogen,

Fremd zieh' ich wieder aus.

Der Mai war mir gewogen

Mit manchem Blumenstrauß.

Das Mädchen sprach von Liebe,

Die Mutter gar von Eh', -

Nun ist die Welt so trübe,

Der Weg gehüllt in Schnee.

Ich kann zu meiner Reisen

Nicht wählen mit der Zeit,

Muß selbst den Weg mir weisen

In dieser Dunkelheit.

Es zieht ein Mondenschatten

Als mein Gefährte mit,

Und auf den weißen Matten

Such' ich des Wildes Tritt.

Was soll ich länger weilen,

Daß man mich trieb hinaus ?

Laß irre Hunde heulen

Vor ihres Herren Haus;

Die Liebe liebt das Wandern -

Gott hat sie so gemacht -

Von einem zu dem andern.

Fein Liebchen, gute Nacht !

Will dich im Traum nicht stören,

Wär schad' um deine Ruh'.

Sollst meinen Tritt nicht hören -

Sacht, sacht die Türe zu !

Schreib im Vorübergehen

Ans Tor dir: Gute Nacht,

Damit du mögest sehen,

An dich hab' ich gedacht.

Translated as (with synposis of whole cycle):

Good Night

As a stranger I arrived

As a stranger I shall leave

I remember a perfect day in May

How bright the flowers, how cool the breeze

The maiden had a friendly smile

The mother had kind words

But now the world is dreary

With a winter path before me

I can’t choose the season

To depart from this place

I won’t delay or ponder

I must begin my journey now

The bright moon lights my path

It will guide me on my road

I see the snow-covered meadow

I see where deer have trod

A voice within says – go now

Why linger and delay?

Leave the dogs to bay at the moon

Before her father’s gate

For love is a thing of changes

God has made it so

Ever-changing from old to new

God has made it so

So love delights in changes

Good night, my love, good night

Love is a thing of changes

Good night, my love, good night

I’ll not disturb your sleep

But I’ll write over your door

A simple farewell message

Good night, my love, good night

These are the last words spoken

Soon I’ll be out of sight

A simple farewell message

Goodnight, my love, good night

OK, just off to leave the dogs baying at the moon.

Saturday 14 August 2010

An orange

On Monday I go away for a week to teach at a residential centre with Pascale Petit, who has just published a book of poems about Frida Kahlo's paintings - the course is in fact about writing from art.

But what does one art have to say about another? Perhaps it is not a question of 'about' at all. Perhaps it is not a commentary or even a conversation, not exactly. It might be no more than a brief electric shock that sends the second art haring off into the distance after some idea of its own. That is what I find now more and more.

But why art in the first place? Why not just the objects of the world, of which there are so many - the objects and processes and events that are the stuff of life. Say, the raising of a hand from a desk. Or the passage of a car past a window. Or some vast idea like the Atlantic Ocean that lives in the head as well as in a locatable physical place?

Something sets the words running and as soon as they start they generate feeling - about the thing that started them, about themselves, about the spaces they occupy, and about the whole sense of simply being here.

There is a loose category of phenomena to which we might apply the word beauty. Certain things are considered, in some sense, beautiful: birth, love, music, death, the Atlantic Ocean - the concept of beauty, the apprehension and expectation of it, hovers over them. The world in them seems concentrated to a purpose. But even small things - maybe particularly small things - can suddenly be full of the world, so much so, that it seems almost too much.

...One day I am thinking of

a color: orange. I write a line

about orange. Pretty soon it is a

whole page of words, not lines.

Then another page. There should be

so much more, not of orange, of

words, of how terrible orange is

and life..

Frank O'Hara, 'Why I am Not a Painter'

A hand rising from a desk might contain all that as it moves from space to language. It is perhaps no more than a kind of yearning for things and language to be perfectly themselves, to occupy as many dimensions as exist.

What the art work provides, the stimulus, which in O'Hara's case is a painting by Mike Goldberg eventually titled 'Sardines', is energy that is not self-referring but outward-bound, as all art is. And maybe it is this concentrated outward projection that draws us to it then kicks us away.

Meanwhile the world goes on happening. People are arrested, charged, imprisoned, killed. A woman in Iran is threatened with stoning. Far away a flood threatens drowning, disease and dispossession. People kick a football about a pitch. Someone in a house a few doors away trips over the stairs. A car draws into the car park and finds a place between two others.

A way of happening. A mouth, said Auden. So the mouth opens and things begin to happen.

Friday 13 August 2010

Kindness

Flicking through the news section of the internet I come across this reprinting of this famous rat-race speech given by Jimmy Reid, in 1972 following his appointment as Rector of Glasgow University the year before.

I remember Jimmy Reid as a figure quite clearly. I was in my early twenties when I became aware of him as the man who led the work-in at the Upper Clyde Shipyard, but that's all in the brief Wiki article I link to above. The point was, he seemed to be the epitome of a good man looming out of what I felt was a dark period.

In the speech he begins by describing alienation in simple human terms; moves on to criticise what was perceived by many, and certainly presented, as normal society, along with the idea of the rat race and the profit-at-all costs motive; considers its effects on the powerless and the unemployed; talks about what might constitute a better society including leisure and education, and ends by quoting Burns's revolutionary poem, 'Why Should We Idly Waste Our Prime:

The golden age, we'll then revive, each man shall be a brother,

In harmony we all shall live and till the earth together,

In virtue trained, enlightened youth shall move each fellow creature,

And time shall surely prove the truth that man is good by nature.

It is the language of the time (Hungarian readers of Petőfi will recognise it immediately), full of confidence and idealism. It is the last line that has always presented difficulties. 'And time shall surely prove the truth that man is good by nature.' We point, as we most often do, to the terrible cruelties of humanity and can scarce believe humanity to be 'good by nature'. Even if we suggest that we start off good then become bad we are left with the problem of how this happens, in other words, how evil enters the world and why, as a popular book had it, 'is everything shit?'

Clearly I am not about to answer this, but want to look at it another way.

I finished reading Sheena Iyengar's book The Art of Choosing (I featured a video clip of her lecturing earlier) and thought it very interesting and intelligent as well as playful, and, finally, deadly serious, but it was her Acknowledgements at the end that led me to this post. We are used to the corny thank you speeches at the Oscars and regard them - well, I do - with a certain weary horror, as if something genuinely valuable were being presented as glitter. Iyengar's thanks are not like that. They are long and detailed - they are specifically for specific kindnesses she has received at the hands of various specific people who had helped her in her research. They are genuinely touching without being sentimental.

I have been the recipient of a great deal of kindness in my time - I don't mean from people doing what they are professionally obliged to do, though I am grateful for that and some have far exceeded their obligations - but from people who were not obliged to do anything. The reasons for their kindness were mysterious. They owned those reasons and may hardly have known the reasons themselves. We can do good things for perfectly selfish reasons. Maybe we just like the idea of ourselves as generous-spirited persons in a position to dispense a little patronage now and then. Who doesn't like a little self-flattery, which always sounds much better coming from others? Maybe we expect thanks for our kindness, chiefly from those who have received it, but also, perhaps, from God, or our pacified guilt or superego. Maybe kindness is self-interest after all.

Actually, it doesn't matter. The benefits of kindness to those who have been kind are theirs to work out. The point is the effect on those who receive, or, as Bob Geldof once put it:' Give us your fucking money.'

We may then go on to argue that being a regular receiver of kindness is a form of humiliation, eventually breeding resentment, or- if we are of a Gradgrindish disposition - that receivers of kindness become uselessly dependent and a drain on the hard-working, charitable rest (the hard-line Tory argument, and the bottom-line hunch of the privileged generally).

Yes, but that is all by the by. It may be so, it may not be so. Both motive and effect are complex. The miraculous good thing is that kindness exists at all. For my part, as a receiver of kindness, I did not only receive the advantages that the kindness of others bestowed on me, but also - far more importantly - I received a model of the world.

Kindness exists as a model, a pattern in the mind (and heart if you want the full mind-and-heart set) that may be chosen. I don't mean charity, if by charity we understand simply the rich giving to the less rich, either as sop to conscience under strain or as tax incentive. Kindness is simply the possible that may be chosen at any time for whatever reason. It is a willed gesture and has to be so. It is the point at which the imagination may move towards Burns's line by an active effort of the will.

Acting kindly will not prove Burns's contention, but it shows the contention is important. How do you become brave? people have asked, often to receive the perfectly sensible and practical answer, By acting as though you were.. How do we prove that man is good by nature? By acting as though we were.

Nothing else required. Except courage - which you acquire by...

The two greatest virtues in the world: courage and kindness, either of which is diminished without the other. Solzhenytsin has it somewhere in Cancer Ward, where I first read it. It's a difficult model, but what other model is worth having? Or at least aspiring to?

In any case, RIP, Jimmy Reid.

Thursday 12 August 2010

Picasso at the Gagosian

This is an absolute joy, but first a brief observation.

It's the Mediterranean, post war Picasso, the family's own collection on show in London, and it confirms an earlier, slightly dormant feeling of mine that the formal set-pieces of the period - in other words the paintings - tend to be an assembly of what, by then, were mannerisms; the compositions still bursting with energy, but in much the same way each time and therefore a little dull, a little dutiful (one must make Art!) a little easy, sitting too contentedly in a visual language he could master without effort.

Maybe he was feeling a little trapped by his own language.

It would be easy to be trapped in his colour. His colours and his paint texture have never been anything to write home about. He isn't nor ever has been a colourist: frankly I don't think he cares about colour. He keeps slapping on the same reds, blues greens and yellows, with a patch of grey here and there, just to push his patterns forward or back. Colour is, of course, secondary to drawing. He is one of the greatest masters of drawing that has ever lived. He can't draw bad lines. Things look clumsy but balance perfectly. His abbreviation-language for limbs and torsos has nothing to do with actual proportion, but the bodies have grace and weight and completeness beyond academic precision.

As for texture, he slaps paint on flat, probably straight from the tube, and stirs it around a without great enthusiasm. Texture, in Picasso, is secondary to pattern, of which he is also one of the great masters. He loves stripes and dots and splodges and cross-hatching, and little frilly edges. They mix languages through spikiness or curviness or frantic activity or silence. They are a world of comedy to him. And delight above all.

But the greatest delight is to be found in the small throwaway fribbles (the cardboard masks, the tiny blobby statues, the splodgy ceramics) and in the magnificent assemblage sculpture. Picasso seems happiest playing against the odds with materials that have no great artistic tradition. He wants to draw in space and to discover what happens when he does so; he wants, in effect, to be less portentously Himself, less what he already knows 'Picasso' to be; more fantastical, more formally mobile. The material of the wooden, cardboard and bronze assemblage statues tease him by resisting. Line, which is Picasso's domain par excellence rediscovers itself through laughter, just as his actual caricatures do.

Someone will tell me, most earnestly, that his art shows him to be mysogynistic - his women being sexual objects cut into violent shapes and that what this means is that he, like all men, genuinely wants to violate women and tear them limb from limb. The same people tend not to say this when the male figures are cut up in the same way, but maybe they'll get round to that. When informed of these solemn facts, I will reply with the greatest pleasure imaginable:

I don't give a damn.

Let me repeat that:

I don't give a damn.

Pleasure is what I take from this exhibition. I have never smiled so much in an art gallery. Smiled? Almost laughed. Life is funny and majestic and savage and childlike and spectacular. Absolute joy.

England versus Hungary

A match report from your Anglo-Hungarian correspondent, the man at the pitch side.

It turned out to be pretty good-humoured as affairs go. We were 18 rows up on the East side (enclosure B if you want to know) about half way between the half-way line and the goal, with the main body of Hungarian supporters just to our right. We made the bad mistake of being hungry before the match at about 6.30 or so and bought two hot dogs plus a cup of tea inside the stadium which set us back about £10.50. Service was friendly (almost everyone on the stadium staff seemed to be Asian) but the hot dog was a sausage in a piece of dry roll that I would normally have paid someone to take away. The tea was overfilled and as we were getting to our seats a couple of people were wondering if we had taken their seats - we hadn't, they couldn't read the numbers on their own tickets - the paper cup simply crumpled in my hands and I had a scalded left hand that threatened to swell into nasty blisters. I found my way back to the food stall and they gave me a cup full of ice that I nursed for an hour or so.

To boo or not to boo

That might have been the most heroic act of the night, but then - somewhat later - along came Gerrard to score two goals that snatched the glory from me. The Hungarians were far more vocal than the home crowd throughout. Our row was half Hungarian as was the one in front of us, and they kept up a steady intermittent chanting. The English girl and her partner on the other side of C were of the subdued, occasionally-booing persuasion.

When the teams were announced there was a mixture of cheers and boos for each individual player. Ranking them in order of disapproval, Ashley Cole undoubtedly topped the boo-list in terms of unanimity and decibel count, followed closely by John Terry, then a little further behind, Frank Lampard, with Stephen Gerrard, Wayne Rooney and Gareth Barry vying for the wooden spoon. Indeterminate little boos for them, as though no-one really wanted to boo them but felt they ought to, the boos, however, roughly equalled by the cheers. Cole was the only player to receive the distinction of being booed every time he touched the ball in the first half an hour.

Half-time was generally greeted with boos, though England were bright in the first twenty-five minutes or so. Changes in the second half brought cheers and some confusion. No Cole, no Terry, no Lampard? What was the point of coming to the match if you couldn't boo them? Were there other players on the pitch? Why couldn't they get off and let the guilty simply stand there in the centre circle a while or do a few laps of the pitch so you could concentrate on the boos? What is football coming to?

When Rooney left the pitch he received a few more half-hearted boos but some cheers too. The fact is people rather like him. When Gerrard finally left he was given a standing ovation - but he had scored two great goals by then.

The couple next to C were dutiful booers but their hearts weren't in it. The girl was in ecstasies when Gerrard scored his first. She was generally smily throughout whenever I looked her way, so the whole thing was a kind of pantomime that had to be got through. She - like most of the crowd including the main, more determined booers - really wanted to like the team, though it is obvious they find Cole and Terry particularly hard to like.

Lots of girls and children at the game. Over 72,000 people.

*

The papers seem to be saying 4-3-3 but the truth is Rooney was up front pretty well on his own in the first half. He didn't look particularly happy there, or at any time. He wasn't particularly mobile either, though that improved as the first half wore on. We thought he'd scored after three minutes but it turned out to be offside so his mood didn't lift. I am not at all convinced he is a spearhead centre forward - he is much better moving onto a defence rather than with his back to it, and that became clear once Zamora was introduced in the second half. Rooney was moving freely and was almost enjoying himself. He wants to be active and involved and is a marvellous passer of the ball. I would always play him just behind a big, strong, fast, or alternatively small, nimble, fast centre forward. Rooney and Zamora looked a good combination. My impression was that Rooney wasn't looking forward to this game but it had to be done and over. Life will go on from here for him

Zamora did extremely well when he came on. He had control, was fast and threatening, could hold the ball up, and drew the defence whichever way he went, clearing space for Gerrard when Gerrard's own position changed in the second half. Zamora was a definite plus. Persevere with.

Gerrard was decent in the first half though stuck out on the left (!) to leave Lampard and Barry holding the middle. Once moved into a more central advanced position in the second half he looked far better. The first goal was a long range curler into the top right, the second was hard to see from where we were but looked damned clever. But he was buzzing in the area about ten yards from the box, picking up loose balls and passes. I hardly dare say it but he looked better once Lampard was off and he no longer had to stick to the left-sided plan.

It was hard to tell about Adam Johnson as he was generally on the far side of the pitch. Missed a good chance early on and that might have affected him. He took all the dead balls and was not wonderfully impressive, but grew into the game as it went on and looked ever more confident and dangerous. Another one to keep and persevere with. I think he has terrific potential.

Kieron Gibbs took the place of Cole and was remarkably impressive. He won his tackles, made good runs, was fast, beat people and linked very well with both Young and, later, Milner. I wouldn't worry about the left back position for a while. He is slighter than Cole but looks just as gifted. Definitely to persevere with.

Theo Walcott was wonderful much of the time. He clearly had the beating of his man, moved inside or outside with ease, was fast and dangerous. Potentially a great player. I suppose he had to be replaced with Ashley Young if Young was going to get a game, but Walcott is the more gifted. Young was good though not quite as good as Walcott had been. Lacks confidence.

Jagielka looked comfortable with or without Terry beside him. He got into a bit of a muddle with Dawson once or twice once Dawson had replaced Terry (who had been all right, but then he wasn't up against a particularly fast forward line). The Hungarians did threaten in the second half and the defence came under strain. Glen Johnson, who seems a rather mercurial player, now wonderful, now dangerously poor, did well enough. but once the Hungarian team started switching positions and running off each other, it wasn't out of the question that they'd score again - and almost did when Gera, the best of the Hungarians, got through one on one but Hart saved.

Hart looked fine though there wasn't much for him to do. He has to stay there now and be number one.

Who have I missed? Milner was busy when he came on, Wilshere had seven minutes. Barry was good enough as a defensive midfielder. For me, the most memorable performances were Walcott, Gibbs and (second half) Gerrard's. General conclusion? I would play as follows, first choice then alternatives in brackets:

Hart

G. Johnson (?)- Jagielka (Ferdinand)-Terry (Dawson /Ferdinand)-Gibbs (Cole)

Barry (Lampard /Wilshere)-A. Johnson ( Lampard /Young)

Gerrard-Rooney

Walcott (Young)-Zamora.

G. Johnson (?)- Jagielka (Ferdinand)-Terry (Dawson /Ferdinand)-Gibbs (Cole)

Barry (Lampard /Wilshere)-A. Johnson ( Lampard /Young)

Gerrard-Rooney

Walcott (Young)-Zamora.

That is a revolutionary 4-2-2-1-1, in other words a form of Christmas tree based on 4-4-2, that becomes 4-3-3 when either Gerrard or Rooney move right up. Occasionally, on very confident days, even 4-2-4. Play Gerrard central high up the park, Rooney switching with him, just in front of him ideally, one wide player high, another wide player moving back. I think Adam Johnson is potentially better than Milner.

When they appoint me as the next England manager I will put the plan into action with alacrity and success (or vice versa). There is the basis for a very good young team there without the baggage.

The Hungarians could be proud of themselves. A little weak in the tackle, a little too easily pressurised. but some nice fast skill in attacking midfield, moving into advanced positions when necessary, a couple of fairly tricky wingers (they've always got those) and an excellent captain figure in Gera. What they need is a more solid defence and one or two more substantial, confident, intelligent and aggressive midfielders. They have great travelling support so things may be looking up.

This from London, from Tom's flat. Off to Picasso at the Gagosian later in the morning before heading for home.

No blisters on left hand and England formation solved for the immediate future. A good day on the whole, and much better than expected. Thank you Tom, Helen and Rich!

The booing? The whole thing was a lot milder and more amiable than I had anticipated. But that is the England crowd at Wembley. It's a family occasion, as they say, a day at the Panto. Nothing too vocal. Not in front of the children or the ladeez. Very much a twenty-first century crowd. The Hungarian support has an air of potential Seventies about it. A touch of the New Nationalism that I have yet to get a feel for in the football context.

Wednesday 11 August 2010

To boo or not to boo is a terrible question

So today we are off to London to see the match, and last night's late radio and this morning's early radio has ben busy discussing whether to boo the team or not.

First off, I loathe lynch mobs. Others clearly enjoy them. I never will.

Some say they have paid so they have a right to boo. Well if they paid to see the earlier matches before the world cup then they had no reason to boo. Maybe, if they happened to have paid to be in South Africa they were entitled to boo - then. Even so I would not have joined them, not if I had paid twice the sum.

Some think the booing is a punishment. Fine. The booers punishment will be that ever fewer people will want to play for the national team. Why should they? Several have withdrawn already. On this occasion a few young untried players will be playing for the first time. Their first taste of playing for their country will be to be booed or greeted with silence. They didn't play in South Africa and they will not be encouraged to play now. Best get them off on the right foot.

Those players who remain in the team are the main core of the team for the next few years. Perhaps they should be punished by never being invited to play again. So take out Gerrard, Lampard, Terry, Cole and Rooney. Do without them. Then live with it. Gerrard, of course, has said he too would boo if he were in the crowd. Fine, then boo Gerrard. My already low respect for him diminishes by the day, which does not mean he is not an outstanding footballer or that I would not pick him.

And Fabio, of course. The press have turned on him as they do on everyone in the end. They torture, chew, then spit out the managers one by one in rapid succession. The press are only interested in triumph or disaster. Nothing in between is interesting. Second is nowhere, third is even more nowhere. They don't want a 'successful' or 'respected' team. They want World Champions or European Champions. The rest is nothing. Capello was great before South Africa - he is a pathetic dolt now.