Back late from Bristol yesterday, a full day for

The Poetry School on the material referred to in the last post. In fact the last post was the first sheet of a set of some forty sheets of an anthology I made for the occasion, but, as with all such anthologies, for use on possibly other occasions, some individual items from it have been drawn from other such self-made anthologies. My entire poetry teaching life has been full of specially compiled anthologies that branch out from each other and sometimes overlap.

The anthology simply moves through the various possible pronouns as well as reference by function or office (the Driver, the Bellman, Herr Doctor, the Headmaster) and proper names. It begins with John Heath-Stubbs's poem,

Use of Personal Pronouns: A Lesson in English Grammar, and Ágnes Nemes Nagy's

Journal, which is comprised of short poems employing

you, I, he / she (Hungarian has no gendered pronouns) all to refer to a single first person figure, with

they as opposition. The

I section begins with Dickinson, moves on to Plath, Whitman, Simic, Shapcott (as a cow) and Hughes (as an otter). I won't try and go through the contents but the idea is to explore the dimensions of usage. Various forms are involved, including, at the end, clerihew and acrostic. I know very well I am not going to cover all the poems in any such anthology but it's like presenting a world in which we can point to various locations.

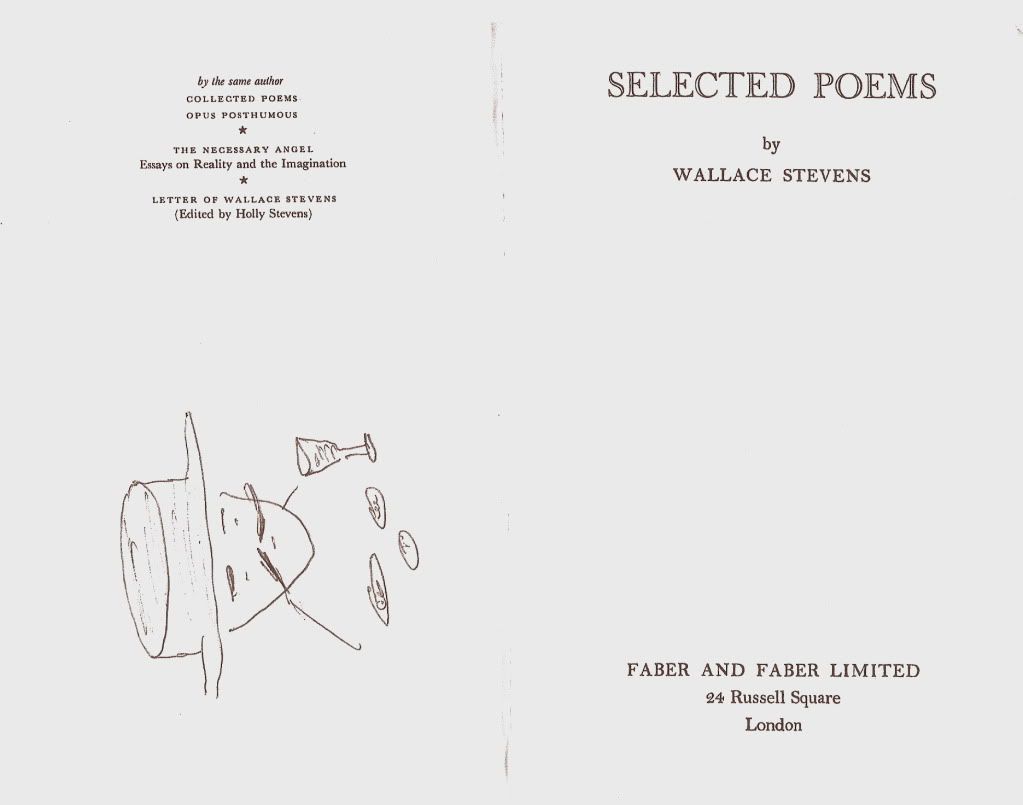

First, however, the reading of a few early sections of Wallace Stevens's

The Man with The Blue Guitar, by way of prayer or grace before meal.

But why? Why this exploration of the uses of identity and consciousness? How does it help?

My hope is that it might serve to relieve a little of the burden on the imagination.

Because poetry is generally short and constantly in danger of seeming insubstantial on the one hand, and portentous on the other; because the common perception persists that poetry is the poet's peculiar way of wearing the poet's great, self-conscious heart on the poet's particularly fancy sleeve; and because the heart, that great metaphorical organ, is certainly in there somewhere, more, so to speak

in the sleeve than

on it, the weight of responsibility can be crushing, or at least distorting for a poet. The very title, poet, is enough to create a vacuum in nature, or at least clear certain rooms, even in the poet's own sense of purpose.

I would like to argue for a certain lightness of heart, for a certain irresponsibility, for a certain understanding of the

gravity of play - not in the Martian sense of the 1980s where everything was fancy, everything was like anything else, everything was potential freshness without the ballast of content (content as the heart that might well resemble a slab of steak on a butcher's counter and be no more than a visual pun hoisted to metaphysical level) - so not in the form of post-metaphysical whimsy, as some, if not all of it, now seems to me, but as nimbleness of sorts, so that there might be different ways of drawing fingers across that blue guitar.

I would like to reduce the expectation in the writer of having something particularly weighty to say. I would like the weight to be found unexpectedly in the engagement with language so it is like something landed in your lap. It would be like finding a mysterious coin in your pocket or handbag. You don't have content (the weight of your heavy heart) and find a form for it, you simply learn to increase your acuity, to develop your ears and sense of touch so, when language moves around you, you have some intuition regarding where you are and where something valuable might be.

I don't mean the writer should simply announce, like John Cage,

I have nothing to say and I'm saying it, and that is poetry as I see it, though that is, in one important sense, absolutely true. True it is, but it itself is a kind of cliché, all too easy on the ear. Not all nothings are alike, and if one nothing is different from another nothing, that is - is it not? - something. And we ourselves are - are we not? - something.

Because the human heart (to use a cliché) is full of clichés. It loves to repeat its own wise saws and mutter its comforting mantras. It likes to reassure itself that it is good and warm and beating: a proper presentable human heart. That it is a heart at all. It wants to reassure itself and the hearts around it, that it has been in the dark places and returned alive, an ancient mariner, a sadder and a wiser man rising the morrow morn. But it wants to produce the goods before it has completed the mariner's voyage.

The poet's voyage is through language by way of the imagination with all its possible freight of meanings.

Relieving the imagination of the sole weight of

me with

my baggage of wisdom and wise saws is much the same as laying down, for a while at least, a monstrously heavy piece of what seems to be vital baggage, an old trunk that weighs a ton even when empty (and it never is empty). Try another piece of luggage and see where it takes you. Try this face, this door. You don't need to be carrying that huge weight around. Try skipping. Try dancing. Try making this peculiarly complicated structure as if it were something you could live in. As if there were a

you.

We don't matter much in the galaxy, but then what else matters? Language is an impossibly leaky system of control, but what else do we have? There's no such thing as four minutes and thirty-three seconds of silence but it's well worth listening before putting a few notes down on the score, to listen, in effect, as if there were nothing but silence. Then playing in delight and darkness.

Listening and playing are valuable acts. Your hands are far too full of luggage to allow for much play.

Many hands make light work. So

they say. So

we might assume.

You might give it a thought, as

one does. As

he, she, it and

they have done, and might do again at any moment.

I am only trying to lend

you a hand.

A little anthology about the heart might be another fine mess to get into.