The second, concluding part of my replies to Berkan Ulu. The answer to question 2 is framed in personal terms but I include it because I suspect certain elements of my answer may address general ways of approaching the sonnet.

2) While composing your sonnets, what sort of technical aspects do you take into consideration with regards to, again, the traditional ways of sonnet writing? And if you don't mind, how/why?

In the Bible Christ explains that the Sabbath was made for man and not man for the Sabbath. Putting aside the specific religious context, what that says to me is that we are not made in order to conform to rules, but that rules are there to serve us.

To continue with the room / spatial metaphor, I first have to decide whether the poem I am about to write is likely to be a sonnet or not. Sometimes I have already decided this, maybe because it relates to other sonnets or is part of a sequence, maybe because I have an instinct that the broad theme in my mind might usefully occupy such a space (I can be, and have been wrong on that). After the first two or three lines I have a clearer idea as to what kind of sonnet it is likely to be - what furniture, what light, what colours it is likely to require.

The idea of colour is interesting because it was the theme of colour that took me deeper into sonnet territory. The colour sonnets begin in Portrait of My Father in an English Landscape (1998). I was so struck by a jar of Monastral Blue pigment in an artists shop that I sat down to write about it, and a sonnet is what came out. After that I wrote dozens more colour sonnets, some in sequence, all on the associational aspects of colour. Some of them were variations on the Shakespearean model - see Sap Green, Chalk White, Romanian Brown - but others used different models. The book ended with three so-called Hungarian sonnets or crowns of sonnets, each consisting of fifteen linked sonnets where the last line of the first became the first line of the second and so on until the fifteenth, which is a sum of all the previous fourteen first lines. The colour sonnets have continued since through all the other books. I might yet write more. Bad Machine (forthcoming January 2013) will contain a double sonnet of which the first part consists entirely of the names of colours, almost all of them invented.

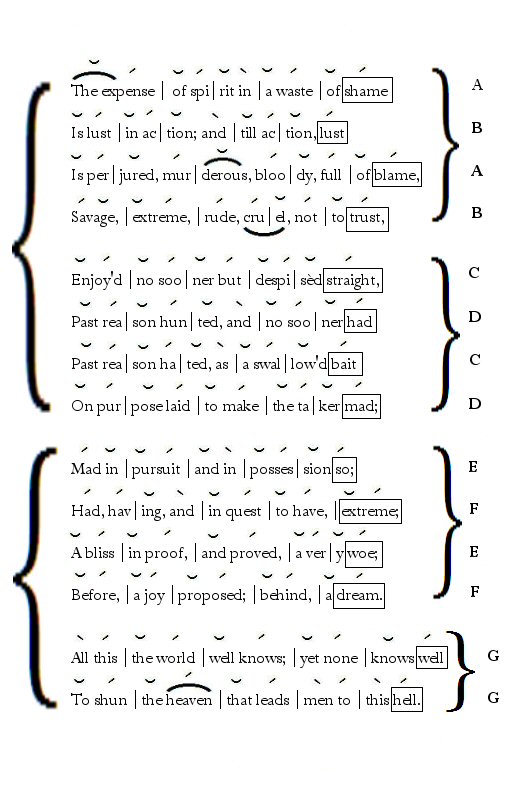

The key is this. I learned how to move inside the rooms and soon I was moving freely enough to understand what could be done within such a room. I could tell when I was in the middle of the room, and when I was within touching distance of the walls. I didn't keep looking back at the classical models - the core of the force field - I could feel them there and know that they were informing my own sonnets with their history. I take care of space, proportion and rhyme. If I know roughly where I am that is what really matters.

*

3) To what extend do you make use of free verse or would you agree with the idea that it is the new "vogue" (or "key" to) of writing sonnets?

I suspect that a good constraining form is at its most powerful when the movements within it seems to be free while the form itself is on the point of breaking. That gives great tension to a poem, such a tension being, I strongly feel, a credible, if provisional, response to life. The end-stopped, highly stable sonnet has its place (I have written a few of these), but it implies a greater stability in experience than I usually feel. The sonnets with the greatest stability tend to contain an element of irony.

In general then, to answer your question one way, the sonnet is a mixture of freedom and constraint and a term like free-verse seems a little beside the point. Free verse - that essentially early 20th century innovation - is no more free than any other verse. It still has to decide where to end a line and when to bring the poem to an end. It has to navigate its way from a beginning and through the body of the poem.

I do write free verse of course - I am currently collaborating with Carol Watts, who comes from the avant-garde tradition (which is the way I now think of it) which is mostly in free verse and partly in open sentence structure. Carol is very good and a great pleasure to work with: her work prods me to a different kind of invention, for which I am grateful.

The dangers of the unconstrained are prolixity, self-indulgence and sheer lack of originality: there is nothing to prod the average poet into invention (see my argument above re necessity and invention). Great free verse - and free verse can be marvellous - is very difficult because the constraints it requires may be endlessly, or carelessly, deferred.

The problem with the average poem - whether formal or free - is that it is insufficiently challenged to invent.

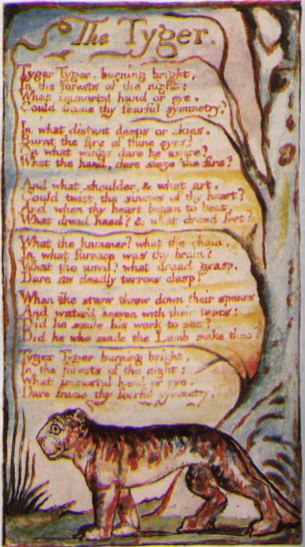

I don't know about vogue. I think certain forms are more useful than others, depending on the times. That may be because a new outstanding example of use has suddenly invigorated the core model, or because current practice has neglected a particular form that is in fact appropriate for the climate of feeling and thought. The sonnet is particularly useful for reasons I have tried to explain: the multivalent core, and the freedom of movement it offers within its room-like shape (we continue to inhabit rooms, they form a lasting comprehensible environment).

And maybe there is something about a lyric poem that tends to find itself within 10-16 lines, that is to say in loose' sonnet' territory. Having said all that, I remember the first line of Wordsworth's sonnet that begins: 'Scorn not the Sonnet; Critic...' In other words the critics had been scorning it - it had become an old relic. Then Wordsworth revives it and we are off again.

.jpg)

.jpg)